| The Folk Music of Chance Electronics:

Circuit-bending the Modern Coconut By Qubais Reed Ghazala |

|

School age Ghazala |

|

I was expected to follow the course of my parents - Masters degrees in this and that, graduating with honors and so on. I did try. But I was bored. Very, very bored. It was, perhaps, in third or fourth grade that I was summoned to the front of the class. Instead of being glued to the blackboard, as was expected of educable students born in the 1950's, I'd been spotted head-down at work with my pencil. "And bring that!" my teacher scolded, pointing at the drawing I was about to leave behind. Drawing in hand I approached the teacher's desk. The class around me was hushed. "Give me that!" she demanded, taking my drawing and staring at the jumble of lines. The confusion on her face was obvious to everyone - this was not the rocket ship or cartoon she expected. A couple giggles broke out from the kids behind me. "What is this?!" she said sternly, flustered, and barely in control. I whispered, nearly ready to cry, "It's an endless maze." I will tell you now what I should have told her then: I was bored. Instead I offered to demonstrate the maze. "Do you want to see?" I said, thinking I might get out of trouble if I explained things and certainly not realizing how much trouble I was about to set in motion. Nodding a "yes", a slow yes, my teacher handed me the maze. I placed the maze on her heavy oaken desk, an invader next to her black books and purple mimeographed lessons, and reached into my pocket. The disapproval on my teacher's face worsened. My schoolmates, usually a noisy bunch, were dead-silent again because this was very strange. If called to the front of the class the determination was usually swift. Leaving the nickel behind in my pocket I removed the remaining two cents of my "milk money" and held the pennies in my clenched fist above the maze... a maze that at that moment had no beginning or end, a piece of paper filled edge-to-edge with continuous maze, homogenous and without distinguishing feature. Just corridors twisting, overlapping here and there, crowding the paper as though pressed for space, all the while purposeless with embarkment and destination points unknown. I dropped the two pennies on the maze and they spun. Pirouetting in my graphite jungle they finally settled to finish the maze, creating at the same moment a surreal map of my destiny. "Now there are start and finish points," I explained, "and every time you drop the pennies you have a new maze." In my teacher's silence I ran the new maze with my eyes. "May I keep this for a few days?" she asked, her tone now very polite. It was one of my best mazes, but I agreed and was dismissed to my seat. Through a sea of awed faces I sulked to my desk and, missing both the irony and prediction of this incident, began to plan the next maze, or some other page I'm sure, in my "problem student" dossier. As mentioned, I was tested and counseled and encouraged and interviewed

and on and on and on. Nonetheless, I've always looked at the world outside

the school window as my fantastic personal laboratory, a stupendous

learning environment all by itself. And it has always been to its flasks

and lessons that I've felt most welcome, and within them most fulfilled.

|

|

Ghazala's

childhood home and the house where bending was born Ghazala's

childhood home and the house where bending was born |

|

The starting point of this maze was a few years past my grade school experience. I was in junior high school, but only barely. The rabbit hole was in my bedroom charading as my wooden multi-drawered desk. In the main drawer was a magic lamp that I knew well, but had not rubbed correctly to meet the genie. It is rare, Aladdin might agree, to hear the genie before taking sight of, but this is how the oracle came to me - in abstract musical apparition. What happened? In a rush to find a forgotten item for a lost-in-time project, and somewhere during the psychedelic 1966-7 "Summer of Love" era, I closed my desk drawer and the world changed. I'd fallen down the hole and I heard the genie call in oscillating waves luring me inside the lamp. Or was it the sirens of Ulysses, I might ponder now, drawing me again to dangerous shores? In my drawer a small battery-powered amplifier's back had fallen off,

exposing the circuit. It was shorting-out against something metal causing

the circuit to act as an audio oscillator. In fact, the pitch was

continuously sweeping upward to a peak, over and over again. |

|

Ghazala's high school desk |

|

| I was a penniless teenager. I'd heard a few synthesizers on recordings.

But at fifteen years old and fundless, owning one was not in my near

future. Here, though, in this shorted-out mini amp I had discovered a

sound source within my means to explore synthesis and experimental music. I soon modified the amplifier in numerous ways. Placing the circuit

within a larger housing, I added rotary switches to the short circuit

paths so I could run the new circuits through various resistors,

capacitors, diodes, photo cells, and any other electronic component I

could find. Potentiometers and push-buttons were added. I discovered

places on the circuit that, if touched, would make the circuit howl: I

then added body-contacts. Not knowing I was building patch bays I built

patch bays. I even added a tiny spinning speaker system. |

|

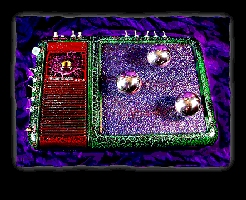

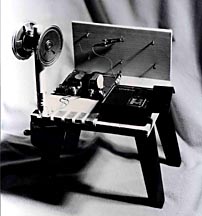

Re-creation

of Ghazala's first circuit-bent instrument. Re-creation

of Ghazala's first circuit-bent instrument. |

|

Turning the rotary switch sequenced these sounds and created rhythms of these unusual voices. Waving a hand over the photo cell gently swept the pitch and animated the sounds. If the body contacts were touched during any of this the voices could be pitch-shifted downward until nothing but clicks or upward until out of hearing range. |

|

A chain of people could "play" each other's bodies using the body contacts. If you broke the chain with your partner, closing the chain again by holding hands, or stroking an arm, or kissing (or any way to vary the contact of flesh) would play the instrument.

No one had seen such a thing before at my high school. The box now had a

couple dozen controls and a set of cables for the patch bay. There were

chrome finger contacts, several dials, and speaker grille cloth cut from

my orange plaid bedroom curtains. |

|

Reed

Ghazala, Gary Dumford, Vicki Mastranardo and cookie truck Reed

Ghazala, Gary Dumford, Vicki Mastranardo and cookie truck |

|

Truth be told, at home in my basement lab I was learning more about electronics, music and synthesis, than my high school could offer at any grade level. I learned endless valuable lessons as this first instrument was built and re-built over those early years, housed and re-housed into different enclosures. Further, as I began to chance-modify other sound circuits I became aware of what seemed to be a new world of music, intriguing and endless, just moment away. I was exploring chance electronics. While simple, the process is

explosive in startling audio output. Fantastic aleatoric music might

result composed of either "real" instruments (samples) or layers of

evolving indefinable sounds (new synthesis). When working with human or

animal voice synthesizers new musical languages might appear. Perhaps less

dramatic but no less intriguing are the original tone colors that might

result, turning that $2 discarded keyboard into something you will gladly

place in your studio. |

|

|

|

|

When satisfied with the collection of discovered circuit paths they are finally "hardwired" into place. This is done by wiring each new circuit through its own switch, a toggle switch that you mount on the instrument's case. Using the switches you can now actuate the effects you discovered with the traveling wire. Plus, now you can combine the effects by turning several switches on at once. I should also note that once the tiny speaker is bypassed the new "line output" will usually produce fine frequency range and fidelity. We've entered a world where music, in theory, circuit design and composition, no longer adheres to human presumption. Thus, great new sounds and musical realities can happen here as you sit with your out-of-theory instrument, your truly alien instrument, and listen to its metamorphosed output. After all, you now have an instrument that exists nowhere else in the universe and can present you with sounds no one else has yet heard. Not that I don't appreciate the music lab's environs, even adore a good

system or module. I do! And not that I'm uninspired with the results of

the theory-true synthesizers I design from scratch, such as my Vox

Insectas or human voice generators. Wonderful instruments! Appreciated as

well are the complex polyphonic instruments I've built from kits or

schematics adhering strictly to design (and music) as we know it. Still,

I've personally found more truly new sounds to listen to, to ponder and

work with by week's end, through chance electronics. "As we know it"

...changes. |

|

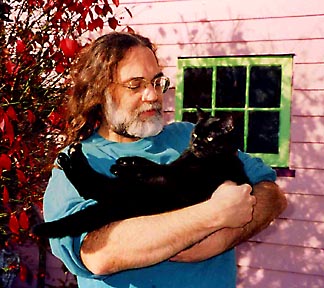

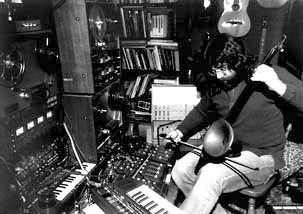

| Ghazala in home

experimental music studio playing an English Phonofiddle, mid 1980's |

|

I am surrounded by instruments - every catastrophe in my house sounds musical. My total collection nears five hundred including many unusual instruments of the world, antique through modern. I'm fond of everything in the planet's instrumentarium (and play Chinese er hu as often as electronic instruments). It is because of this, perhaps, that I recognize the difference. Chance-wired instruments take you to a new place. |

|

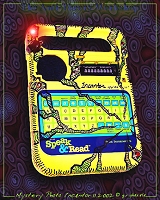

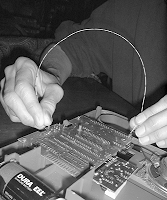

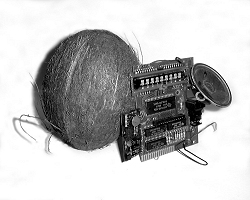

Ghazala's

first Incantor prototype made from the first Speak & Spell available to

the public.

Ghazala's

first Incantor prototype made from the first Speak & Spell available to

the public.